China has once again called India a “partner, not a rival” in 2025, as both nations seek to rebuild trust after years of border tensions and strained ties post-Galwan. From troop disengagement in Ladakh to trade talks, high-level meetings, and easing of restrictions, this article explores recent diplomatic shifts, historical flashpoints, and the geopolitical balancing act shaping India-China relations.

China Calls India a Partner, Not a Rival

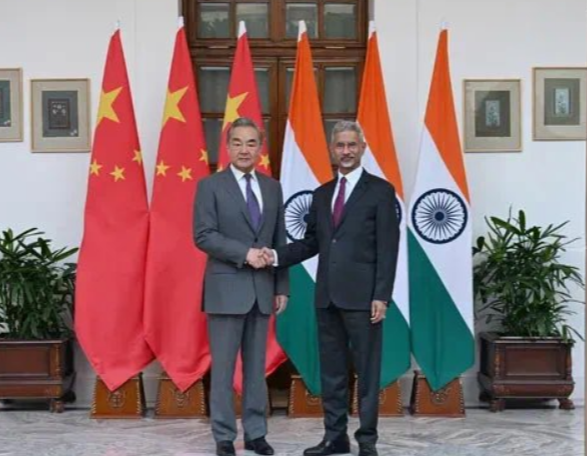

China has once again framed India as a “partner rather than a rival,” signaling a diplomatic recalibration after years of mistrust. On August 19, 2025, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met his Indian counterpart in New Delhi and emphasized the need for a “correct strategic understanding” between the two neighbors. He urged both countries to view each other through the lens of partnership, not rivalry, while highlighting the importance of cordiality and mutual benefit.

This statement comes amid renewed efforts to stabilize bilateral relations that have been strained since the deadly 2020 Galwan Valley clash. The new outreach aligns with recent troop disengagement agreements, high-level meetings, and attempts to boost trade and people-to-people ties.

Diplomatic Engagements and De-escalation

The August 2025 visit by Wang Yi is part of a broader push for engagement. In October 2024, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia. This was their first formal dialogue since the 2020 border clash, and it marked a thaw in ties as both leaders expressed a willingness to reset relations.

In December 2024, the 23rd Meeting of Special Representatives on the India-China border issue was held in Beijing—the first in five years. This meeting reopened the high-level dialogue mechanism that had been frozen since Galwan. Looking ahead, there is speculation that Prime Minister Modi may travel to China in 2025 for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit, further raising hopes of renewed engagement.

On the ground, October 2024 brought a breakthrough as both sides agreed to disengage troops in Depsang and Demchok, two friction points along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh. While the agreement did not resolve the larger territorial disputes, it reduced tensions by creating buffer zones where troops cannot patrol. This pragmatic step reflects both sides’ desire to avoid escalation—especially as China faces an intensifying rivalry with the United States and India navigates uncertainties in U.S. foreign policy under President Trump.

Economic Cooperation and Trade Shifts

Beyond the border, economic ties are also under review. India is considering easing restrictions on Chinese investments that were imposed after Galwan. A proposed clause would exempt companies with up to 10 percent Chinese shareholding from requiring government approval, a move designed to attract global firms that rely on Chinese supply chains.

Trade remains a central pillar of the relationship. In 2024, bilateral trade reached $127 billion, with China remaining India’s second-largest trading partner. Despite concerns about trade imbalances, India continues to depend heavily on Chinese imports, including rare earth minerals vital for manufacturing.

At the same time, India has seen success in its own manufacturing sector. Mobile phone exports surged 42 percent to $15.6 billion in 2023–24, with Chinese suppliers playing a role in Apple’s iPhone assembly in India. This cooperation underscores how economic interdependence continues despite political frictions.

Visa and travel facilitation are also improving. Direct flights are being restored, visa restrictions have been eased, and in June 2025 China allowed Indian pilgrims to visit holy sites in Tibet. Talks are also underway to reopen three trading posts along the LAC, another symbolic step toward normalization.

Historical Precedents of the “Partner, Not Rival” Narrative

China’s current rhetoric is not new. In 2012, following India’s successful Agni V missile test, China’s Foreign Ministry stated that India and China were not rivals but partners. Later that same year, on the 50th anniversary of the 1962 war, Beijing reiterated this message, stressing that the two countries shared more common interests than disputes.

Even in 2022, Chinese Ambassador Li Jiming echoed similar sentiments, denying that Beijing viewed India as a strategic rival. These statements reveal a recurring pattern: Beijing often employs conciliatory rhetoric during sensitive moments or when it seeks to manage tensions with New Delhi.

A Complicated History

The India-China relationship has always been layered with mistrust. The 1962 Sino-Indian War over Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh created deep scars that persist to this day. Subsequent clashes, such as the 1967 Nathu La confrontation and the 1987 Sumdorong Chu standoff, reinforced the volatility of the border.

Despite these flashpoints, there have also been milestones of cooperation. In 2005, the two countries signed the Strategic and Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Prosperity, aimed at boosting trade and stability. In 2006, the Nathula Pass was reopened for trade after 44 years. But the deadly 2020 Galwan Valley clash reversed much of the progress, leading to bans on Chinese apps in India and tighter scrutiny of Chinese investments.

Today, the border remains unresolved, with about 50,000 square miles of disputed territory. China continues to claim Arunachal Pradesh, while India claims Aksai Chin.

Geopolitical Rivalries and Strategic Balancing

Beyond their bilateral issues, both countries are competing for influence across South Asia and the Indian Ocean. India has extended a $100 million credit line to the Maldives for infrastructure, directly countering China’s earlier investments such as the China-Maldives Friendship Bridge. China’s close partnership with Pakistan, including military cooperation, remains a significant concern for New Delhi.

At the same time, both countries are active in rival international groupings. India leans toward the Quad with the U.S., Japan, and Australia to counter Chinese influence, while China leads the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, platforms such as BRICS and the SCO provide rare opportunities for dialogue.

The U.S.-India-China triangle further complicates matters. India has deepened ties with Washington to counter Beijing, but uncertainties under the Trump administration—such as threatened tariffs on Indian exports—have forced New Delhi to hedge. China, meanwhile, sees improved ties with India as a way to balance U.S. pressure. Analysts have described this delicate relationship as a potential “dragon-elephant tango.”

Conclusion

China’s renewed framing of India as a partner rather than a rival reflects both pragmatism and strategic necessity. While mistrust remains high, particularly on the border and in regional influence battles, recent developments suggest a cautious attempt at stabilization. The disengagement agreements, high-level dialogues, and economic recalibrations highlight that both sides recognize the costs of confrontation.

Whether this latest phase of outreach leads to a lasting reset remains uncertain. History suggests that such rhetoric often fades with the next crisis. But for now, India and China appear to be inching toward a fragile balance—caught between rivalry and partnership in an era of shifting global geopolitics.